Another glassworks - John Baker's - was situated next to the river, on land now occupied by the MI6 building immediately north of Vauxhall Bridge. The excavation of this site is the subject of a fascinating Museum of London monograph No.28 - see the link at the end of this page for further details.

More Detail

Glass-making was first introduced to Britain by the Romans, who started blowing glass into moulds, thus allowing a wide variety of shapes to be made, including the first glass windows around 100 AD. Indeed, the Italians, and particularly the Venetians, remained pre-eminent in the glass industry for many hundreds of years. They originally made their glass by heating silica (sand) with sodium carbonate ("soda ash"), although many glassmakers eventually used potash (potassium carbonate) in place of soda ash. (Soda ash and potash are the major components of wood ash, but also occur as mineral deposits.)

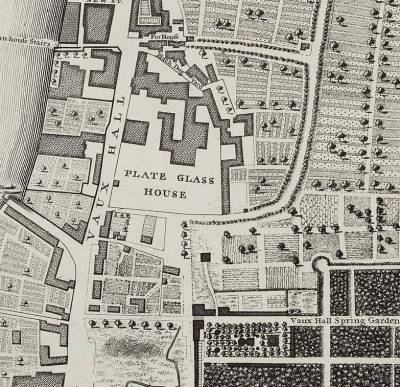

The Venetians protected their technology very successfully, including when working abroad, and grew rich on its proceeds. But foreigners began to challenge Italian dominance through various innovations from the 1600s onwards. For instance, a British patent was granted to Sir W Slingsby in 1610 for burning coal instead of wood in glass furnaces. The use of wood was then made illegal in England and, in 1617, Sir Richard Mansel acquired the sole rights for making glass throughout the country. Most monopoly rights and patents lapsed during Oliver Cromwell's Protectorate (1649-1660) but, in 1663, the Duke of Buckingham, although unable to obtain a renewal of the monopoly, secured a ban on the importation of much specialised glass, thus paving the way for his own investment in glass-making in Vauxhall (1670) and Greenwich.

But Buckingham faced increasing competition from lead crystal ("flint glass") which was invented by English glassmaker George Ravenscroft in the 1670s by substituting lead oxide for part of the potash then used to make high quality glass. Buckingham's Greenwich glass house was forced to close soon afterwards but Vauxhall carried on, employing Venetian craftsmen to make mirror glass, up to about 1 metre long, until around 1780.

|

|

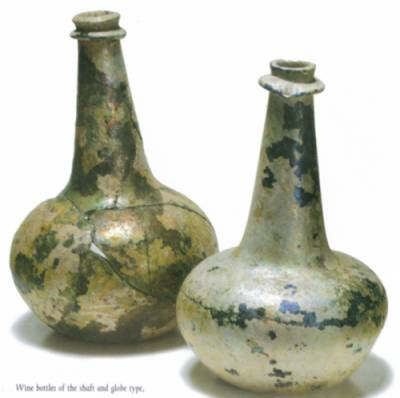

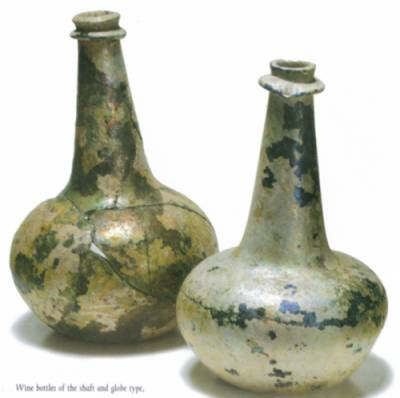

As noted above, another glassmaker, John Baker, built a glass house near what is now Vauxhall Bridge some time before 1681. One of his products was wine bottles - pictured right - manufactured in response to the new fashion, from c.1650 onwards, of serving wine in bottles, one of major changes in beverage consumption, including coffee drinking - the first coffee house opened in 1652 - and tea drinking - first experienced by Samuel Pepys in 1654. Around the same time a third glassmaker, John Bellingham, returned from Holland to begin making "Dutch" lead glass in Vauxhall in 1671, initially in partnership with, and soon in separate premises from Buckingham.

|

It is possible that Vauxhall's glass industry encouraged the Dollond family who opened an optician's shop in Kennington in 1750. They invented the achromatic lens, using two different types of glass (common "crown" glass and the more expensive - and hard to make - "flint" glass) to cancel out each other's colour distortion. Their dominance in telescope manufacture was ensured because English flint glass manufacturers exported only lower quality flint glass to the Dollonds' overseas rivals. The Dollonds' business merged with Aitchison & Co in 1927 to form Dollond & Aitchison, the well-known high street chain of opticians

|

|

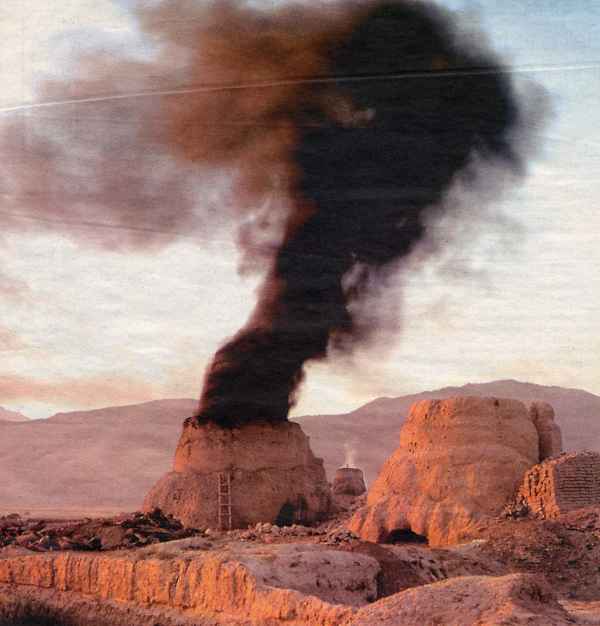

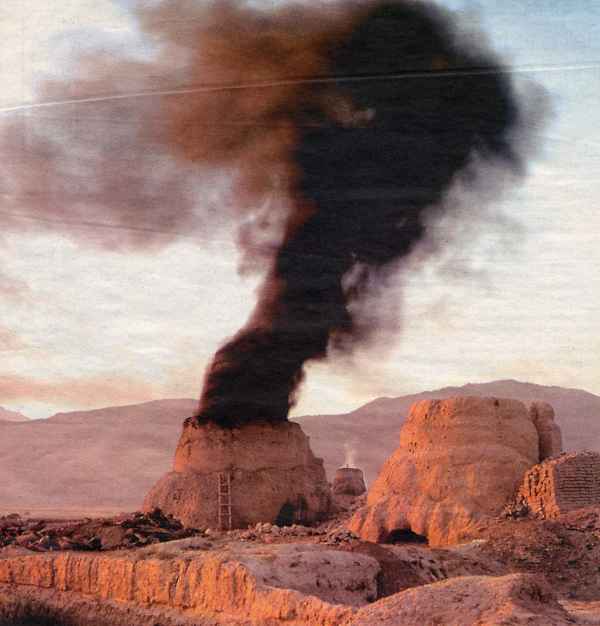

Why Vauxhall? In part, this was because glass works fumes were highly polluting. The picture to the left - of a modern day brick kiln in Afghanistan - graphically shows how much smoke was developed by such primitive industries. Glassmaking was therefore prohibited anywhere near the City of London. Also, the nearby river was also very useful for transporting coal and sand to the works.

|

Buckingham, by the way, was quite a character. He was a royalist who benefitted after the restoration from his prior support for Charles II . And he favoured religious toleration, earning the respect of William Penn, the Quaker who went on to found Pennsylvania. His highs included being reputedly King Charles II's richest subject and later being appointed Chief Minister and then Chancellor of Cambridge and High Steward of Oxford Universities. His lows, however, were many. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London at least twice and his tenure of high office was said to be chiefly marked by scandals and intrigues. He left children, but none of them were legitimate so his title died with him.

Interestingly, from Vauxhall's point of view, Buckingham dabbled in chemistry ("a chymist") and this probably led to his interest in glassmaking. Overall, however, he was judged (including by himself) to have wasted his life. He was said to be "A man so various that he seemed to be not one but all mankind's epitome: stiff in opinions, always in the wrong ... Was chymist, fiddler, statesman and buffoon". And on his deathbed he declared "O! what a prodigal I have been of that most valuable of all possession - Time!"

|

|

The Museum of London sells a very interesting monograph (pictured left) following the excavation of John Baker's 17th century Thameside glasshouse in Vauxhall.

|