Vauxhall, the Oval and Kennington

The Aylesbury Estate lies to the East of the Walworth Road and North of Burgess Park, and - as can be seen from the above photo - within sight of the skyscrapers of the City of London to the left and Docklands to the right. But the estate reflects the hopes of another age. Built over 28.5 hectares between 1967 and 1977, the maze of towering blocks, low-rise flats and concrete walkways was an attempt by 1960s planners to save the less fortunate from the south London slums. Indeed, it was part of a futuristic plan to link estates between the Elephant and Castle and Peckham with linear walkways which would separate roads from the elevated pedestrian passages. It was probably the biggest such estate in Europe, and Nikolaus Pevsner, the architectural historian and critic, called it "the most ambitious postwar development by any London borough".

The above second photo was taken in 2014 from a nearby park and after the completion of The Shard at London Bridge which can be seen to the left of the photo. Note the double rainbow.

|

|

The ideas which led to the creation of the estate were originally based on a fascination with ocean liners. In his hugely influential 1923 polemic, Vers une Architecture, the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier showed thrilling illustrations of liners to demonstrate how superior these were to most contemporary buildings. Then, in 1933, Ciam (Congres Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne), a pressure group of the most zealous European moderns, drew up its Athens Charter on board the liner SS Patris. This committed Ciam members to designing rigid functional cities characterised by high, widely spaced apartment blocks separated by broad green belts, and had a profound impact on postwar public authorities across Europe. Le Corbusier himself, so often blamed for all dismal concrete estates, designed his showcase Unite d'Habitation in Marseilles. This great 12-storey concrete ship of domesticity (pictured left) was meant for blue-collar families. Today it is home to white-collar professionals. It works because it is well planned and thoroughly serviced, containing a shopping street and a hotel. |

In Britain, however, we implemented the Athens charter too quickly, too cheaply, too brutally and without the necessary skills. The vast Aylesbury and North Peckham estates were therefore never built with such thought, nor served with such care. The idea of living in ship-like buildings, as the successful Barbican estate in the City of London proves, is not a fundamentally mad or bad one. But the result in South London, some decades on, was described as follows by the South London Press:-

Prime Minister Tony Blair had aspirations for the Aylesbury. Only hours after his election in 1997, the Prime Minister rushed to the estate to make its 7,500 "forgotten people" a symbol of New Labour's determination to tackle social exclusion. The estate then benefited from government assistance by being declared a "New Deal for Communities" area. In 1999 it was given a budget of £56m from which £46m was to be spent on major capital works. The funding was much needed. More than half the residents were on housing benefit; one in five households had no wage earner; overcrowding was three times the national average.

In 2001, residents were urged to allow the estate to be transferred to the ownership of a private housing association but they rejected the plan with 73% against. Officials and residents have been trying to find another way forward since.

The then Conservative Party leader, Michael Howard, visited the estate in 2004 and accused Labour of failing to keep its promises. Accompanying newspaper reports dubbed the Aylesbury "the estate from Hell".

Plans were then made to redevelop the whole estate - replacing a total of 2,700 dwellings with around 4,000 now ones. But Southwark Council could not afford to do it on their own; they were already heavily committed to redeveloping the Elephant and Castle area. They accordingly sought financial help from the Greater London Authority and the Government's Homes and Communities Agency (HCA). The first new homes had been completed by late 2010 but the HCA then announced that it no longer had the funds to continue supporting the larger project, whose future became uncertain.

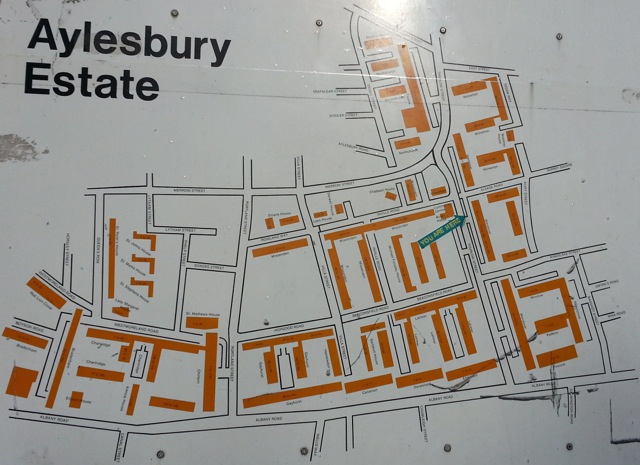

Here is a plan of the estate: