Although the Luftwaffe's attacks on London during the Second World War failed to force Britain into capitulation, they destroyed over one million buildings, left 30,000 Londoners dead, and over 1.2 million homeless (out of the two million displaced across Britain, with many devastating air raids on other cities).

About 2,500 bombs, V1 pilot-less flying bombs and V2 rockets fell on Lambeth, many of them in Vauxhall in an attempt to hit key infrastructure etc. along the river:- the railways, the Thames bridges, the power stations (Bankside and Battersea), gas works and food stores.

The bridges, in particular, were so important that an additional temporary bridge, known as Millbank Bridge, was built 180m downstream of Vauxhall Bridge opposite the Tate Gallery (see photo above). Millbank Bridge was built of steel girders supported by wooden stakes. Despite its flimsy appearance it was a sturdy structure, capable of supporting tanks and other heavy military equipment.

The rest of this note looks at:-

- recycled ARP stretchers,

- the Kennington Park bombing,

- the Richborne Terrace and Fentiman Road bombings

- one of the few remaining Anderson air raid shelters,

- the capture of a German airman at the Oval,

- the bombing of Freemans Catalogue HQ,

- the spoof recruitment of Air Raid Wardens, and

- V-2 rocket bombs, ... and

- provides links to further information.

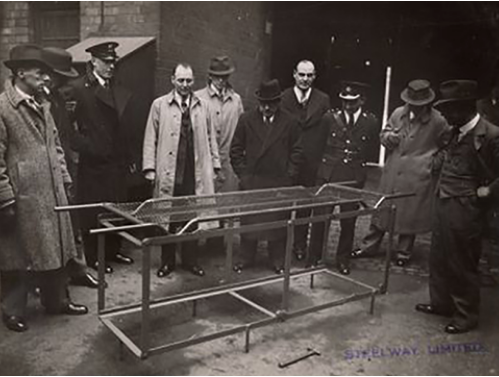

Recycled Stretchers

Possibly the most obvious reminders of the bombing are Vauxhall and Kennington's post-war housing estates which were built on the extensive bomb sites. It is particularly interesting to spot the many fences around the estates which were made from redundant ARP (Air Raid Precaution) stretchers. The black and white photo is of a demonstration by their manufacturers - Steelway. Further information can be obtained from the Stretcher Railing Society.

..

..

Kennington Park Bombing

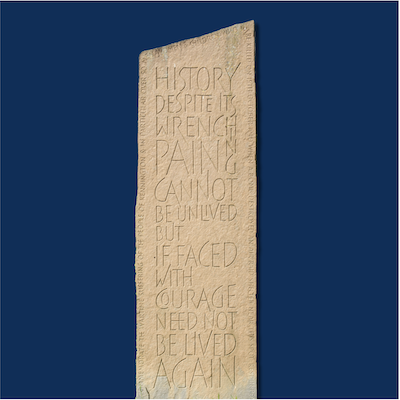

"History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage need not be lived again."

Another poignant reminder of the bombing is the memorial in Kennington Park to what was by far the worst local incident in the war:- the bombing of the Kennington Park communal shallow trench-style air raid shelter on Tuesday 15 October 1940.

The shelter was large enough to accommodate hundreds, and maybe thousands, of people, and it filled the whole of the south field in Kennington Park - the field opposite what is now the cafe. The outline of the buildings can still be seen from the air, especially when the ground is very dry - see the photo below. But the shelter was an unpleasant place, and people only went there because the government stopped them going down into the nearby underground stations. One witness reported that "The public shelter was horrible, smelly. It had a mouldy slab of concrete for a roof. But you couldn't go anywhere else - the Oval Station was full of barbed wire - they wouldn't let you near it."

The direct hit on the shelter inevitably caused huge damage and horrible injuries. One witness reported that he "was 17. My job was helping to dig the bodies out. We put curtains up, so that people walking past couldn't see in the pit. Eventually we couldn't do anymore and we covered the remains with lime.".

The chaos of war along with the need to keep up morale meant that no official toll of those dead and missing was announced, but historians now believe that 104 people were killed. It is said that 46 bodies were recovered but the majority of the bodies were left unrecovered when the site was leveled.

A more detailed report may be found in Rob Pateman's excellent pamphlet "Kennington's Forgotten Tragedy". There is a memorial in Lambeth Cemetery to these and other WWII civilian deaths.

Richborne Terrace, Fentiman Road, Rita Road & Usborne Mews

There were two major bombings in Richborne Terrace (which then extended through to Meadow Road). Bombing on the night of 27/28 September 1940, led to the demolition of Nos 34-60, subsequently replaced by maisonettes. Amazingly, only nine people were killed. Much later, in 1945, a V1 flying bomb (see also further below) landed north west of Carroun Road.

There were two major bombings in Richborne Terrace (which then extended through to Meadow Road). Bombing on the night of 27/28 September 1940, led to the demolition of Nos 34-60, subsequently replaced by maisonettes. Amazingly, only nine people were killed. Much later, in 1945, a V1 flying bomb (see also further below) landed north west of Carroun Road.

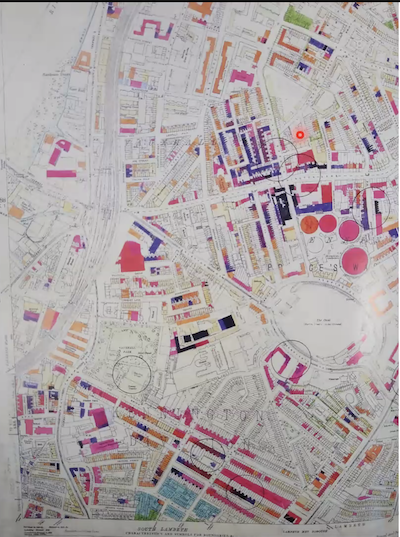

Click on the thumbnail to the left to bring up a larger version of this extract from a London Councils' map of WW2 bombing. The darker the colour, the worse the damage. The circles show where V1s landed.

(The map appears to show that a V1 landed where the maisonettes are now. This is either incorrect (V1s did not appear until 1944) or else that V1 landed later in the war where there had already been significant damage.)

The first bombing was recorded, in words and a picture, by local civil defence worker Stanley Rothwell:

"There was a vast crater with bodies of women and children strewn in the rubble around its edge, the shelter they had occupied had gone sky high ....... We got busy shrouding the dead and mangled bodies ...... We tried to check the number of people involved but found that there were some missing ..... We found them the following morning lying some hundreds of yards away on some waste ground spread-eagled like taylors dummies; they had been tossed there by the blast, heads and limbs missing. "

Mr Rothwell's painting of the incident is in the Imperial War Museum and is reproduced below with their kind permission. It shows an Anderson shelter after a direct hit. Mr Rothwell is on the left accompanied by his colleague Benny Cunningham. It is interesting that Mr Rothwell's son subsequently went to work in the War Museum.

Most of the Anderson shelters, in the back gardens of the Richborne Terrace houses, were removed after the war. However, the shelter at the back of one house is still in good condition, and can be visited by prior arrangement:- Click here for further information.

The last bomb to fall on Lambeth - a V1 jet-propelled pilot-less "doodlebug" - photo above - landed between Richborne Terrace and Fentiman Road - northwest of Carroun Road - on 5 January 1945. 13 people were killed and 100 made homeless. Here are photos comparing a similar terrace still standing today in Fentiman Road with a photo taken in Fentiman Road after the V1 bombing. Damaged Richborne Terrace houses can be seen in the distance. The whole area is now occupied by large blocks of flats.

Public housing was subsequently built on the site, and some poignant art, commemorating the children killed in the war, can still be seen on two of the blocks. Click here to find out more.

Bombs also destroyed houses in Rita Road - see the photo of the modern infill below - and damaged the coach station which is now occupied by Usborne Mews, between Fentiman Road and Richborne Terrace. Further information is here.

Tragically, many years later, a Richborne Terrace resident, Philip Russell, was one of the victims of the first ever London suicide bombers when he was killed on a bus in Tavistock Square, near Euston Station, on 7 July 2005.

The Oval Airman

There was also an interesting incident near the Oval. The largest and last of the daylight raids on London took place on 15 September 1940. Over 180 German planes were brought down, one of them a Dornier, piloted by Feldwebel Robert Zehbe whose plane developed engine trouble and lagged half a mile behind the main bomber stream. He was set upon by fighters and bailed out, setting the aircraft on autopilot. He landed in front of Alverstone House, outside the Oval in Harleyford Road, his parachute fouling on a telegraph pole, leaving Zehbe some feet from the ground. Superintendent Gillies of Kennington Road Police Station rescued him from what was described as a 'lynch mob'. The police van then drove off, not along the road, for some reason, but across the hallowed turf of the Oval cricket ground before it took the prisoner across Vauxhall Bridge to Millbank Military Hospital. He died from his wounds the following day and was buried in Brookwood Military Cemetery. There was a suggestion that he had been seriously injured by the Oval mob, but it is equally possible that he was badly injured before he landed.

An interesting sequel was that the now pilot-less Dornier was then rammed by a Hurricane fighter aircraft which was low on ammunition and piloted by Flying Office Raymond (Ray) Holmes. The Dornier then entered into a spiraling descent which ended when it crashed in the forecourt of Victoria Station - see the photos below. Pieces of the bomber and are now in the RAF Museum, Hendon. During its spinning dive, the centripetal forces acting on the Dornier caused its bombs to be released, and they hit or landed near to nearby Buckingham Palace, damaging the building. Ray Holmes' plane crashed more quickly, diving almost vertically into the crossroads at the junction of Buckingham Palace Road, Pimlico Road and Ebury Bridge. Ray parachuted to safety, landing nearby.

The by now much diminished remainder of the German bomber force continued its bomb-run, aiming for the railway lines near Battersea Park. Each Dornier's payload of twenty 50kg bombs carved a run 460m long and 23m wide. Some fell on the high-density civilian housing. The bombs missed Clapham Junction but fell across the rail tracks that connected it (a) to Victoria Station north of the Thames and (b) to the main line heading north east to Waterloo on the south side of the river. The bombs cut the tracks in several places and a viaduct collapsed over some rails, whilst four unexploded bombs delayed repairs. But the rail lines were only out of action for three days.

Follow this link to read a South London Press article about the incident.

Ray Holmes' attack on the Dornier was re-created (inaccurately) in the film The Battle of Britain where Ray Holmes was played by Edward Fox. Ray Holmes' own story is told (accurately) in Christopher Jary's Portrait of a Bomber Pilot which provides a detailed and very moving account of the wartime experiences of a British bomber pilot, Jack Wetherly DFC.

Freemans Catalogue HQ

This large office at 139 Clapham Road was bombed in September 1940, killing 23 people. It was subsequently rebuilt and reoccupied by Freemans before being converted into apartments and some retail premises.

Do you want to be an Air Raid Warden?

The war years were certainly not devoid of humour. ARP (Air Raid Protection) and LDV (Local Defence Volunteer) officers were sometimes rather officious and sometimes under employed, so their acronyms were said to stand for 'Angin 'Round Pubs' and 'Look, Duck, Vanish' respectively. And the following link takes you to a delightful spoof letter circulated to his neighbours in Redcross Street (now Redcross Way) by young James Donovan. He was particularly adept at mimicking the bureaucratic style of the time. (If your browser reduces the image to fit your screen, you can expand it by clicking in the bottom right hand corner of the image.)

V2 Rocket Bombs

V2s were 13 tonne supersonic rockets which carried one tonne of explosive. Because they were traveling faster than the speed of sound, survivors reported first hearing the explosion, then the sound of the rocket engine, and then the sonic boom. The first V2s landed in the UK in September 1944 and were a complete surprise. The Government was slow to make any announcement, initially claiming that there had merely been gas main explosions.

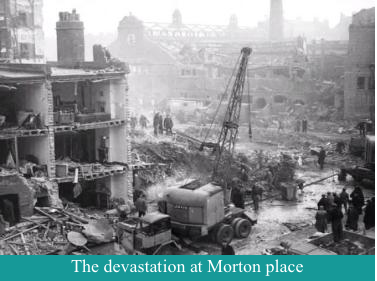

Four V2s landed in Lambeth. One, on Clapham Common, damaged Holy Trinity Church. Two more destroyed houses in Rodenhurst Road and Chatsworth Baptist Church in Norwood. The last V2, and the last-but-one bomb to fall in Lambeth during the war, landed on 4 January 1945, killing 39 people and injuring 70 in and around Surrey Lodge Dwellings and the Lambeth Baths at Morton Place at the north end of Kennington Road. The baths, in Lambeth Walk, were rebuilt and are now a medical practice. The rest of the area was redeveloped in the 1960s as tower blocks.

V1s and V2s were far from cost-effective. The 9,000 V1s and 1,100 V2s fired at Britain, the latter packed with non-reusable cutting edge technology, killed on average fewer than one person each.

Further Information

Further information about the war years in Lambeth can be found in the excellent Life in Lambeth during World War Two published by Lambeth Archives.

And the blitz inspired some amazing public art in Vauxhall.

....

....