Wilson's first candle factory was set up in 1830 in the grounds of a riverside villa called Belmont, which gave its name to the factory. The site, at the foot of Vauxhall Bridge, was later acquired by the Phoenix Gas Works, followed in 1962 by the London Cold Store and a lorry park. It is now St George Wharf riverside apartments. The factory at first made candles the old-fashioned way but using a 'composite' of tallow and coconut fat barged down the river from the company's mill in Battersea using coconuts imported from Sri Lanka. By 1835, however, the new technology was ready and the new cheap, high quality candles became very popular. Indeed, as it was traditional for every loyal household to burn a candle in its front room window on the evening of the monarch's wedding, most people in London lit one of Price's candles on the evening of Queen Victoria's wedding in 1840.

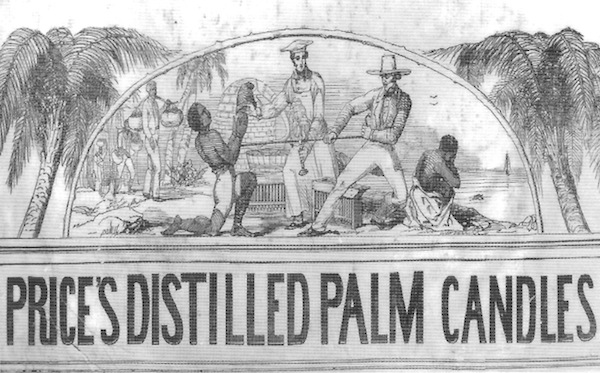

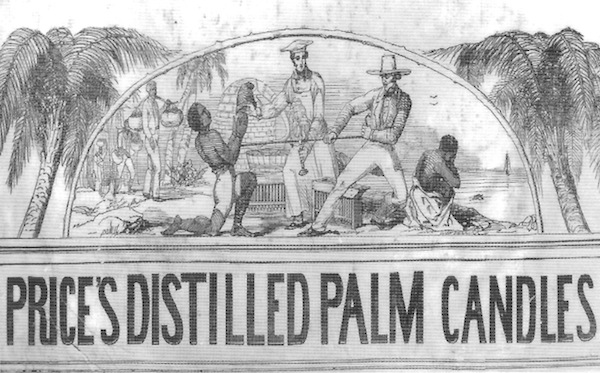

Another innovation was to start using palm tree oil, whose export provided an economic alternative to the slave trade, thus making Price's palm oil candles very "politically correct" and popular, slavery having been abolished in the British Empire in 1838. This virtue was emphasised in the advertisement reproduced above. On the left, Africans bring palm nuts to trade. The slave trader stands centre right with one slave at his right, and another with a rope around him. This man is saved by the candle maker in the centre who is surrounded by the tools of his trade and who is using a palm oil candle to burn through the rope. He is also offering the freed slave the red cap of liberty.

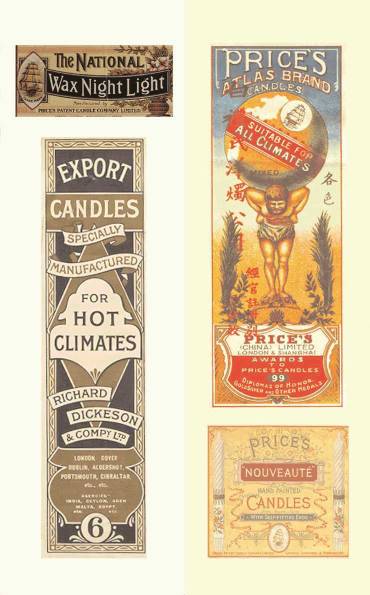

And why "Patent" candles? Price's had made the mistake, in the 1830s, of not patenting their "composite candles" only to see rivals quickly copy their products. After this error they protected all their inventions with patents and in 1847 accordingly changed their name to Price's Patent Candle Co.

Price's soon expanded beyond making candles. First, they began to sell the two by-products of the candle making process:- glycerine (used as a treatment for burns and skin disease, as a food preservative, in paints, etc.) and a liquid fat called oleine which soon replaced olive oil as a light lubricating oil in the still young woollen and cotton manufacturing industries. Prices also soon began to benefit from the creation of the oil industry as they distilled the first petroleum oil discovered in Burma in 1854. Price's distilled the oil to make paraffin wax and so paraffin wax candles, and then started selling the by-products benzene (used for cleaning), kerosene (for burning in lamps and stoves) and heavier oils (for sale as lubricants for machines developed during the industrial revolution).

Price's success caused them to build candle factories elsewhere, principally up the river at Battersea, and in Liverpool. They closed their Vauxhall factory in 1855. By the early 1900s Price's was the world's largest candle manufacturer employing 2,150 people. It was taken over by Lever Bros (later Unilever) in 1919 and eventually changed ownership several times, and moved its UK manufacturing to Bicester, in Oxfordshire.

A more detailed history of this fascinating company can be found at the Price's Candles website and in Jon Newman's booklet The Story of Price's Candles.