Lambeth Walk

Lambeth Walk is a walk, a song, a dance, two films, a photograph, a market and a street in Kennington, London. Read on for further detail.

The original "Lambeth Walk" was an evening promenade by the predominantly poor residents of North Lambeth:- that is the area around Black Prince Road.

The Song

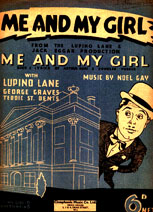

The walk was popularised by Noel Gay who wrote the song Doin' the Lambeth Walk with its catchy tune for the 1937 Douglas Furber musical comedy Me and My Girl. (This musical should not be confused with the 1942 American musical film "Me and My Gal", starring Judy Garland - but note the New York Times' error, below.)

"BRITISH KING GETS LESSON FROM 'LAMBETH WALK' STAR. King George and Queen Elizabeth saw the "Lambeth Walk" show, "Me and My Gal" at the Victoria Palace Theatre tonight. The Queen wore a white slipper-satin gown, a white fox cape and two gardenias in her hair. The King, in evening dress, wore a gardenia in his buttonhole. Both joined in the shouted "Oi" which ends the Lambeth Walk chorus. Lupino Lane, star of the show, was presented to the King and Queen after the performance. "They said they had been walking the Lambeth Walk the wrong way - the ballroom way - and promised to do it our way in the future.""

Me and My Girl was the first musical to be televised, and Lupino Lane went on to play Bill Snibson in the 1939 film of the musical - entitled Lambeth Walk so as to benefit from the popularity of the song.

Lambeth Walk - Nazi Style

1939 also saw the beginning of World War II and in 1942 Len Lye made a short propoganda film Lambeth Walk - Nazi Style which, through ingenious editing, purported to show Hitler and his elite guards marching and dancing to The Lambeth Walk.

The Photograph

The Street & Market

Lambeth Walk is also a street in North Lambeth, between Kennington Cross and the river. It was for many years the site of a thriving street market but it was badly damaged by bombing in the Second World War. (One nearby bomb-site was used in the filming of Passport to Pimlico.) The Greater London Council embarked on a wholesale redevelopment of the area in the 1960s, but the earlier atmosphere was never regained, even though a few shops and stalls continued in its modern new surroundings It has since been the subject of some further controversial redevelopment proposals, as recorded by Michael Ball in the Observer on 7 July 2002:-

"Most of us live in cities. But cities don't work. Transport gridlock, boarded-up shop fronts, crumbling schools without teachers, rampant teenage pregnancies, drug-related crimes.

What's the answer? Call in the regenerators - the local authority, the professional partnerships, the incomprehensible funding mechanisms, the businesses with a conscience. Oh, and talk to the community. Or, rather, get some lowly muggin's signature on your regeneration bid and offer some crumbs from the redevelopment table.

For those of us living in inner-city areas such as Lambeth this is our common heritage. London's employment base was shrinking before the war, and the new tier of bureaucracy resulting from the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act legitimised the trend, driving the great urban clearances. Whole communities, such as those within Lambeth, were transported to the 'overspill' estates and new towns. Streets of slums were redeveloped into brave new housing blocks, pedestrianised shopping centres, high-level walkways, unlandscaped open spaces.

At Lambeth Walk, 2,000 homes, 100 shops, five pubs and one church were replaced with half the homes and shops, one pub, no churches, and a park. There was no discussion of the needs of the community. They were just shipped out. The remaining adjacent estates didn't take kindly to the new communities eventually shipped in.

By the 1990s, Lambeth Walk was considered a failure, dilapidated, with empty shops, low educational attainment and employment. So back came the local authority, but 40 years on they were armed with that essential Blairite tool: a public-private partnership with big-league developers. This time there was some dialogue with the community, but the solutions were similar: the complete razing of the estate, to be replaced by another planner's vision of tomorrow. They call it regeneration, but it is really comprehensive redevelopment by committee. And unlike the original comprehensive redevelopment - which at least got results - no homes have been built, since the local community rejected the proposals. Why? Because they didn't work with the best of what there is: the maturing trees in the park, the youth club, the networks of families and friends that met in the remains of the shopping centre. Teenage pregnancy wasn't addressed, nor was drug crime or youth alienation. And, most of all, it was rejected because the professionals were no longer trusted."

An excellent detailed history of Lambeth Walk may be found here, courtesy of the Partleton family.