Page 4

The Lambeth Ragged School

By the 1840s, the industrialisation of Vauxhall and elsewhere led to such increases in population that many children went without schooling, either because their families could not afford it or because demand outstripped what existing charities could supply. ‘Ragged Schools’ sprang up in poor districts, often in stables, lofts and railway arches, where local working people and well-wishers taught reading, writing and arithmetic on Sundays.

An 1848 report looked at the books of 16 Ragged Schools, attended by 2,345 youngsters between the ages of five and 17. Of these, 162 ‘confessed’ that they had been to prison, many of them several times. 116 had run away from home, and 170 slept in lodging houses, ‘the nests of every abomination that the mind of man could imagine.’ 253 lived by begging, 216 had neither shoes not stockings, 249 had never slept in a bed, and many had lost one or both parents.

In 1849, Henry Beaufoy, owner of the distillery that is now Regent’s Bridge Gardens, established the ‘Lambeth Ragged School’ in Newport Street, where children had once been taught in one of the railway arches. Free, compulsory primary education came in after the Education Act of 1870.One-third of the building remains, home of the Beaconsfield art gallery. The Lambeth Ragged School also taught children a trade and in time morphed into the former Beaufoy Institute technical school around the corner in Black Prince Road.

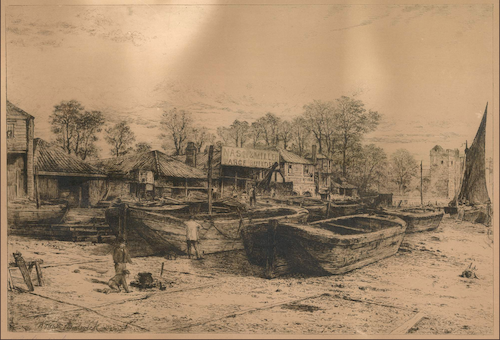

This is a c.1860 etching by Strudwick showing boatyards just downstream from Lambeth Palace. Please click on it to see larger version.

The Slums

Industrial premises near the river were surrounded by very poor quality housing ("slums") which were eventually cleared in four waves. First, there was pioneering work by the Peabody Trust towards the end of the 1890s. Then the Duchy of Cornwall developed its model housing on its Kennington estates in the early 1900s, followed by developments by the London County Council in the 1930s and other council developments in the 1950s to 1970s.

There are some interesting buildings along Renfrew Road, towards Elephant and Castle, including the Lambeth Workhouse where Charlie Chaplin once lived. Follow this link to read more about the buildings.

"This Wheel's On Fire" Julie Driscoll lived, in the mid to late nineteen-sixties, in a small block of Peabody Buildings next to the Black Dog Pub on the corner of Vauxhall Walk and Glasshouse Walk. She was then the lead singer of Brian Auger and the Trinity. Her photo is on the left. That area, that is now grassed over, at the North end of Spring Gardens was a huge thriving community until they bulldozed it in the early 70s. Coincidentally, Julie re-recorded the song in the early 1990s as a theme tune for Absolutely Fabulous which starred Joanna Lumley who now lives around a mile away, albeit in a rather more substantial house.

"This Wheel's On Fire" Julie Driscoll lived, in the mid to late nineteen-sixties, in a small block of Peabody Buildings next to the Black Dog Pub on the corner of Vauxhall Walk and Glasshouse Walk. She was then the lead singer of Brian Auger and the Trinity. Her photo is on the left. That area, that is now grassed over, at the North end of Spring Gardens was a huge thriving community until they bulldozed it in the early 70s. Coincidentally, Julie re-recorded the song in the early 1990s as a theme tune for Absolutely Fabulous which starred Joanna Lumley who now lives around a mile away, albeit in a rather more substantial house.

The Thames has of course always itself been a major transport link, as well as an obstacle. It used to flow much more slowly than now because the many-arched London Bridge bridge acted as a very effective tidal barrier until it was demolished in the early 1830s. Indeed, the flow of the river was so impeded that the water upstream of the bridge could be up to 2 metres higher than downstream. It was therefore possible for boatmen to offer speedy and effective ferry services in rowing boats. And the sluggish river sometimes froze so much during the winter that 'ice fairs' could be held on it.

Another reason for the faster tidal currents and greater tidal range, as well as the demolition of the old London Bridge, is that the river is now much narrower following much building work, including the construction of the embankments. But the underlying river current remains very slow. It takes three weeks for a floating object to travel from Teddington to Southend. The river has in the past been very polluted, and was at its worst in the big stink of 1858, and again when it was biologically dead around 1910. But it is now relatively clean and is now the largest nursery for North Sea fish.

Follow this link to learn the history of local railways, including the Northern and Victoria Lines.

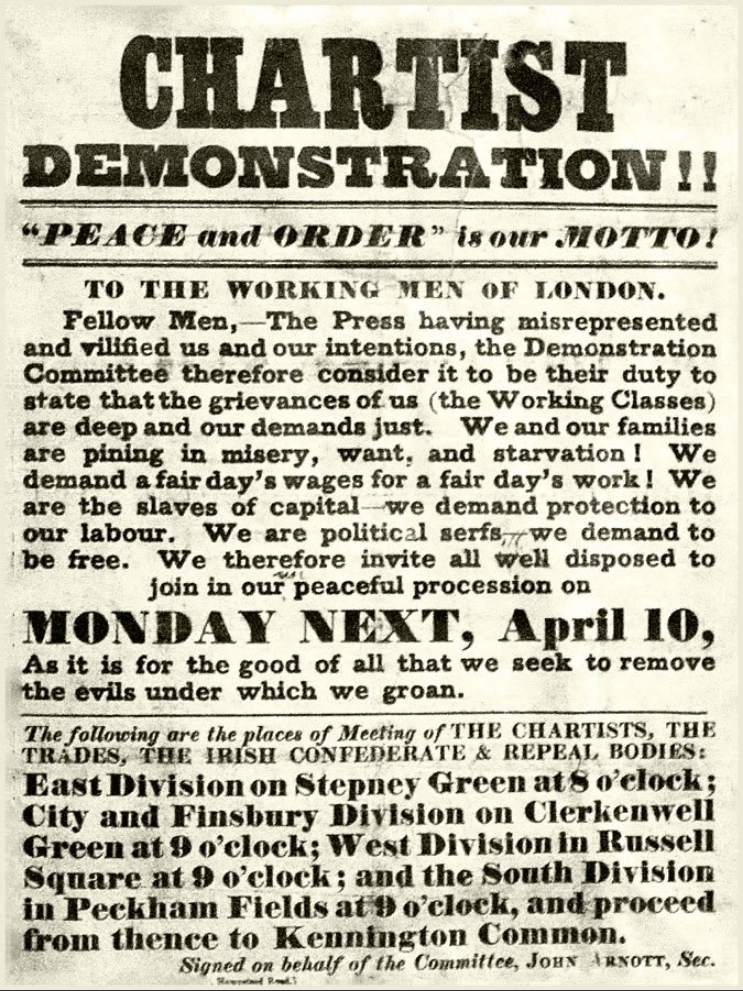

Kennington Common (now Kennington Park) originally extended as far south as South Island Place, between the Brixton and Clapham Roads. It was the rallying point for the Chartists on 10 April 1848. The Chartists' main demands were votes for all men, annual general elections, secret ballots and so on.

The Chartists met in places which had meaning for local people, often common land which had been retained despite the enclosure movement. The Chartists were reaffirming their right to meet in that space, including the People's Green in Glasgow, the Town Moor in Newcastle upon Tyne, and Kennington Common in London.

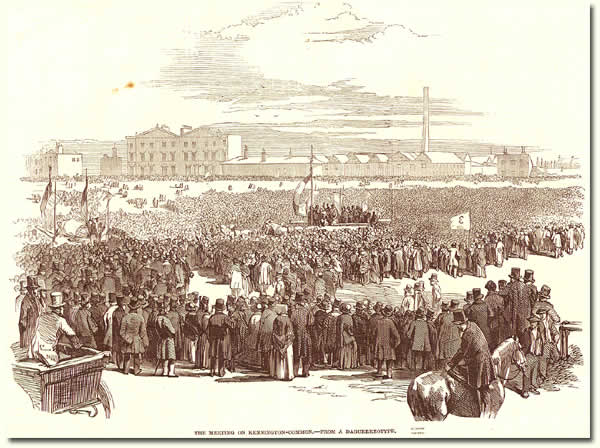

Half a million were expected to meet on Kennington Common and then march on Westminster to present a petition signed by 6 million. Some feared that London might then join a series of revolutions which had shaken mainland Europe. In the event, the Government put on a great, if discreet, show of force, including enrolling 170,000 special constables. One historian reports that "London was armed to the teeth". Only 15,000 chartists dared to assemble and the event passed off peacefully. Interestingly, however, the event was the first large scale event to be recorded by means of the new daguerrotype photography:

The common also attracted preachers (including John Wesley, the founder of Methodism) and crowds of 20,000 or 30,000 sometimes gathered to hear them.

And Kennington Park was the destination for the world's first motorised double-decker bus. It ran from Victoria to Kennington in 1899 ... and of course it was red.

Click here to read a more detailed history of the park.

And click here to read a more about the Chartists and Kennington.

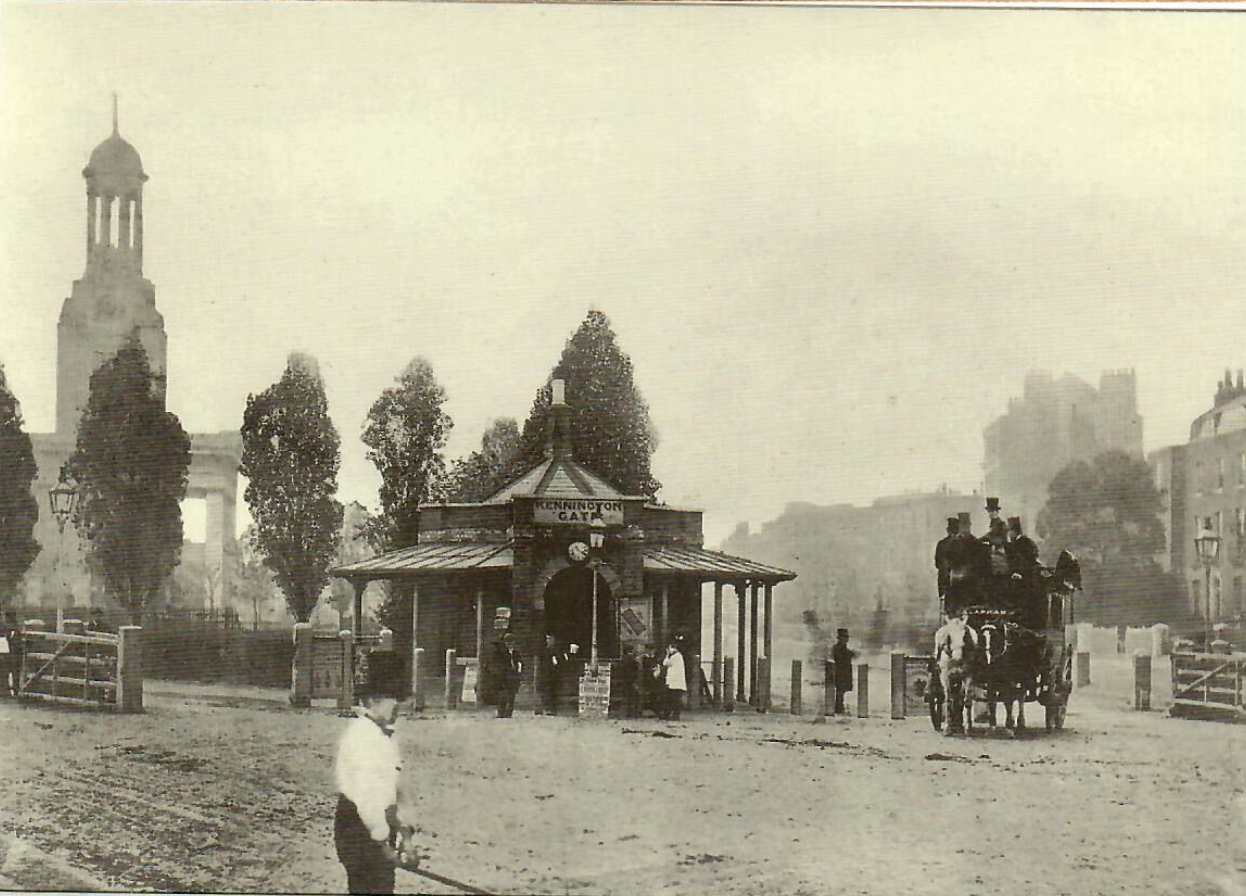

Here is a 1830 drawing of part of the common, looking towards St Mark's Church (see further below).

St Mark's Church, clearly shown in the above picture, and now opposite Oval tube station, was one of the Waterloo churches and finished in 1824. A Parliamentary Act of 1818 provided money to build new churches in the slums "lest a godless people might also be a revolutionary people". The churches were also to be the nation's token of Thanksgiving to Almighty God for the victory at Waterloo, hence their collective name. The monies were in fact mainly spent in the middle-class suburbs and did little to alleviate the acute distress and harsh repression which manifested themselves in such demonstrations as "Peterloo". Indeed, St Marks was certainly not in the slums. The area was semi-rural and its congregation was originally very well off so that the church was supported by "pew rents".

The Kennington Turnpike Gate stood just north of the church, where the roads to Brixton and Clapham diverge. (Turnpikes were long distance toll roads. They lost a lot of income following the arrival of railways, and the last ones were transferred to local authority care in the 1890s.) Here is an 1862 photo:

The St Marks' site was previously occupied by the Surrey County Gallows. The Surrey gallows were famously used in 1746 to hang, and then behead and disembowel, a number of those who had joined "Bonnie Prince Charlie" in the 1745 Stuart uprising. The last person to be hanged at Kennington was John Badger of Camberwell Green, executed in 1799. The last public hanging in the UK - albeit in a gaol - was in 1868.

The Penelope Club, the first ladies-only chess club, was founded in Kennington in 1947.

Click here to read page 5 of this story.

Martin Stanley